Seeing is Believing: the Alex Colville Retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario

Decades ago, when I first began teaching at Sheridan College in suburban Toronto, a publisher’s representative meandered through the warren of desks which housed Sheridan’s liberal arts faculty. The publisher’s rep was searching for contributors to a college level sociology textbook under development by Collier Macmillan. I was a recent arrival to Canada at the time, an immigrant teaching courses on Canadian immigration and learning the hard way about black ice on Highway 401. Without much forethought, I agreed to write the textbook chapter on “minorities” with an expanded focus on ethnicity, race, gender and class in the Canadian context. “Sure,” I said to him. “Why not?”

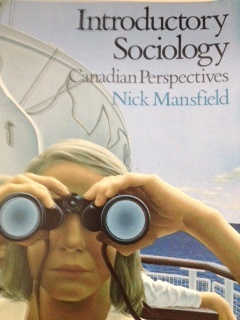

Introductory Sociology. Canadian Perspectives was published in 1982, including my chapter, duly acknowledged, on “Minorities and Race Relations.” I have no idea if the textbook was widely adopted in college sociology courses or not. (For some reason, I didn’t use it in my courses.) And once I received my complimentary copy of the book, I don’t recall hearing from Collier Macmillan again. What remains salient for me, however, is not the content of the book or the size of its readership, but rather the soft cover of Introductory Sociology. It features a woman on a ferry, her eyes hidden behind binoculars. She directs the binoculars directly at us, the viewers, while she herself obscures the man sitting behind her.

Introductory Sociology. Canadian Perspectives was published in 1982, including my chapter, duly acknowledged, on “Minorities and Race Relations.” I have no idea if the textbook was widely adopted in college sociology courses or not. (For some reason, I didn’t use it in my courses.) And once I received my complimentary copy of the book, I don’t recall hearing from Collier Macmillan again. What remains salient for me, however, is not the content of the book or the size of its readership, but rather the soft cover of Introductory Sociology. It features a woman on a ferry, her eyes hidden behind binoculars. She directs the binoculars directly at us, the viewers, while she herself obscures the man sitting behind her.

I didn’t know then that the soft cover of this particular sociology textbook was a detail from Alex Colville’s celebrated painting, To Prince Edward Island (1965), in the National Gallery of Canada. I’m ashamed to admit that I likely didn’t know where Prince Edward Island was in 1982, though I do now. But perhaps the specifics of place don’t matter in a painting as placeless as Colville’s To Prince Edward Island. The painting is more about the act of seeing, imbued with a feeling of curiosity and mystery. It was the perfect choice for a sociology textbook.

When I recently viewed To Prince Edward Island in a retrospective of Colville’s work at the Art Gallery of Ontario, I was struck by the sociological sensibility that runs through many of Colville’s paintings. Any number of his canvasses could serve as the jacket cover for an introductory book on sociology. Woman at Clothesline (1956-1957) features a female figure holding a laundry basket as she steps over dead leaves. The painting captures a transitional moment in the domestic lives of women. Colville’s Pacific (1967) features a man whose head is cropped off gazing out to sea in the background. A pistol lies on a barren table in the foreground. The painting evokes a sense of impending violence. Danger lurks close by. Not surprisingly, Pacific is currently the most requested reproduction of Colville’s work. Likewise, Family and Rainstorm (1955) has dark and foreboding undertones of psychic disturbance threatening the family. All three paintings focus on subjects which have long been the domain of sociological investigation: gender, violence and family.

Colville consciously made art that portrayed contemporary society. Writing to a critic, he once noted: “I think you seem to have expressed my concern for the actual. Also the almost sociological concern with what life is like now.” No aspect of everyday living seemed too mundane for his canvasses. He painted ordinary moments in such works as Woman in Bathtub (1973), Refrigerator (1977), Kiss with Honda (1989) and Living Room (2000). Colville would no doubt have agreed with the sociologist Peter L. Berger who wrote: “Everything that human beings do, no matter how commonplace, can become significant for sociological research.” Colville might simply have added ditto for art.

Did the seemingly mundane figures and events of everyday life that Colville painted become archetypes of the modern condition, as some reviewers of the AGO retrospective claim? I’m not sure. But I do think that Colville, the artist, and Berger, the sociologist, share a primary wisdom: Things are not necessarily what they appear to be. Social reality, it turns out, has many layers of meaning. The discovery of each new layer seems to change our perception of the whole.

Colville’s work, of course, diverges from that of the sociologist in significant ways. Suffice it to say, Colville didn’t need to undertake an ethics review before he began to research and paint human subjects. His most intimate paintings depict his wife Rhoda, dressed and undressed — with her fully informed consent.

So that’s Rhoda behind the binoculars on the cover of Introductory Sociology. Canadian Perspectives.